NORML v. DEA (DC Cir. 1977)

NORML v. DEA, 559 F.2d 735 (D.C. Cir. 1977) (Google)

NORML v. DEA, 559 F.2d 735 (D.C. Cir. 1977) (PDF)

The NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR the REFORM OF MARIJUANA LAWS (NORML), Petitioner v. DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, Respondent.

No. 75-2025

United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit

December 9, 1976, Argued

April 26, 1977, Decided

SUBSEQUENT HISTORY: As Amended.

PRIOR HISTORY: Petition for Review of an Order of the Drug Enforcement Administration.

COUNSEL: Peter H. Meyers, with whom R. Keith Stroup was on the brief, for Petitioner.

Robert J. Rosthal, Deputy Chief Counsel, Drug Enforcement Administration, with whom Jeffrey J. Freedman, Attorney, Drug Enforcement Administration, and Allan P. MacKinnon, Attorney,

Department of Justice, were on the brief, for Respondent.

JUDGES: Wright and Robb, Circuit Judges, and Gesell, [Footnote *] District Judge. Opinion for the court filed by Circuit Judge Wright. Dissenting opinion filed by Circuit Judge Robb.

[Footnote *] Of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, sitting by designation pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 292 (a) (1970).

OPINION BY: WRIGHT

OPINION

[559 F.2d 737] WRIGHT, Circuit Judge:

The present case represents yet another phase in the ongoing controversy between petitioner National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) and respondent Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), an agency within the Department of Justice. [Footnote 1] NORML has been seeking to effect a change in the controls applicable to marihuana under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, 21 U.S.C. § 801 et seq. (1970) (CSA or Act). Respondent DEA has resisted those efforts by citing United States treaty obligations under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, opened for signature March 30, 1961, 18 U.S.T. 1407, 30 T.I.A.S. No. 6298, 520 U.N.T.S. 151 (Single Convention). [Footnote 2] A brief overview of the pertinent portions of those laws is necessary to a meaningful discussion of the background of this litigation.

[Footnote 1] The controversy originally involved the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD), a predecessor agency of DEA. Following a reorganization within the Department of Justice, the case was continued against the DEA Director as respondent. See National Organization for Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) v. Ingersoll, 497 F.2d 654, 656 n.1 (D.C. Cir. 1974).

[Footnote 2] The United States ratified the Single Convention in 1967. For a discussion of the events surrounding that ratification, see Cohrrsen & Hoover, The International Control of Dangerous Drugs, 9 J. INT'L L. & ECON. 81, 84-87 (1974).

I. THE CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ACT

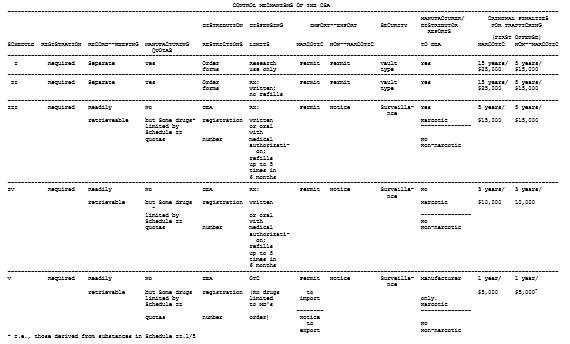

In 1970 Congress enacted the Controlled Substances Act, a comprehensive statute designed to rationalize federal control of dangerous drugs. [Footnote 3] The Act contains five categories of controlled substances, designated as Schedules I through V [Footnote 4] and defined in terms of dangers and benefits of the drugs. [Footnote 5] 21 U.S.C. § 812(b) (1)-(5). The control mechanisms imposed on manufacture, acquisition, and distribution of substances listed under the Act vary according to the schedule in which the drug is contained. [Footnote 6] In drafting the CSA Congress placed marihuana in Schedule I, [Footnote 7] the classification that provides for the most severe controls and penalties.

[footnote 3] See NORML v. Ingersoll, supra note 1, 497 F.2d at 656; Cohrrsen & Hoover, supra note 2, at 88.

[footnote 4] The Act's initial schedules of controlled substances are contained in § 202(c), 21 U.S.C. § 812(c). These listings are subject to amendment pursuant to § 201, 21 U.S.C. § 811, and have, in fact, been amended on several occasions. Cf. 21 C.F.R. § 1308.11 (1976).

[footnote 5] See NORML v. Ingersoll, supra note 1, 497 F.2d at 656; Vodra, The Controlled Substances Act, DRUG ENFORCEMENT, Vol. 2, No. 2, at 36-39 (Spring 1975).

[footnote 6] See generally 21 U.S.C. §§ 822-829, 841-846; Cohrrsen & Hoover, supra note 2, at 90; Vodra, supra note 5, at 2-7 (this author's chart of CSA control mechanisms is reproduced as an appendix to this opinion).

[footnote 7] See § 202(c), 21 U.S.C. § 812(c); 21 C.F.R. § 1308.11. For purposes of the CSA marihuana is defined as follows:

The term "marihuana" means all parts of the plant Cannabis sativa L., whether growing or not; the seeds thereof; the resin extracted from

any part of such plant; and every compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture, or preparation of such plant, its seeds or resin. Such term does not include the mature stalks of

such plant, fiber produced from such stalks, oil or cake made from the seeds of such plant, any other compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture, or preparation of such mature

stalks (except the resin extracted therefrom), fiber, oil, or cake, or the sterilized seed of such plant which is incapable of germination.

21 U.S.C. § 802(15). The definition was carried forward from the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, ch. 533, § 7(a), (b), (c), 50 STAT. 551.

See United States v. Walton, 514 F.2d 201, 203 (D.C. Cir. 1975).

Recognizing that the results of continuing research might cast doubt on the wisdom of initial classification assignments, [Footnote 8] [559 F.2d 738] Congress created a procedure by which changes in scheduling could be effected. Pursuant to Section 201(a) of the Act, 21 U.S.C. § 811(a), the Attorney General "may, by rule," add a substance to a schedule, transfer it between schedules, or decontrol it by removal from the schedules. [Footnote 9] A reclassification rule [Footnote 10] promulgated under this section must be made on the record after opportunity for hearing, in accordance with the rulemaking procedures prescribed by the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. ch. 5, subch. II (1970). Section 201(a) further provides that rescheduling proceedings may be initiated by the Attorney General on his own motion, at the request of the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, or, as in the present case, on petition of any interested party.

[Footnote 8] In § 502(a) (6), 21 U.S.C. § 872(a) (6), Congress expressly authorized the Attorney General to undertake "studies or special projects to develop information necessary to carry out his [rescheduling] functions under section 811 of this title." In addition, § 601 of the CSA, 21 U.S.C. § 801 note, established a presidential Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse and directed the Commission to conduct a study of marihuana and submit reports containing recommendations for legislative and administrative action. See also NORML v. Ingersoll, supra note 1, 497 F.2d at 656-657.

[Footnote 9] Section 201(a)(1), 21 U.S.C. § 811(a)(1), provides that the Attorney General may add a substance to a schedule or transfer it between schedules if he

(A) finds that such drug or other substance has a potential for abuse, and

(B) makes with respect to such drug or other substance the findings prescribed by subsection (b) of section 812 of this title for the schedule in which such drug is to be placed[.]

Pursuant to § 201(a)(2), 21 U.S.C. § 811(a)(2), he may "decontrol" a substance if he finds that it "does not meet the requirements for inclusion in any schedule."

[Footnote 10] "Reclassification" and "rescheduling" will hereinafter be used to indicate any change in the legal status of a substance under the Act - i.e., addition to, deletion from, or transfer between the schedules.

At the heart of the present controversy is the statutory requirement that the Attorney General share his decisionmaking function under the Act with the Secretary of HEW. Specifically, Section 201(b), 21 U.S.C. § 811(b), provides that prior to commencement of reclassification rulemaking proceedings the Attorney General must "request from the Secretary a scientific and medical evaluation, and his recommendations, as to whether such drug or other substance should be so controlled or removed as a controlled substance." The evaluation prepared by the Secretary must address the scientific and medical factors enumerated in Section 201(c), 21 U.S.C. § 811 (c); these factors relate to the effects of the drug and its abuse potential. Pursuant to Section 201 (b), the Secretary's recommendations "shall be binding on the Attorney General as to such scientific and medical matters, and if the Secretary recommends that a drug or other substance not be controlled, the Attorney General shall not control the drug or other substance." [Footnote 11]

[Footnote 11] Moreover, both DEA and HEW have interpreted § 201(b) to bar DEA from exceeding the level of control recommended by HEW. See Vodra, supra note 5, at 34.

Section 201(d) of the Act, 21 U.S.C. § 811(d), contains a limited exception to the referral procedures detailed in Section 201(b)-(c). Subsection (d) provides:

If control is required by United States obligations under international treaties, conventions, or protocols in effect on the effective date of this part, the Attorney General shall issue an order controlling such drug under the schedule he deems most appropriate to carry out such obligations, without regard to the findings required by subsection (a) of this section 12 or section 812(b) of this title [Footnote 13] and without regard to the procedures prescribed by subsections (a) and (b) of this section.

The issue that has produced the widest gulf between the parties is the effect of subsection (d) on the decisionmaking procedures triggered by NORML's petition to decontrol or reschedule marihuana. Respondent argues that where, as here, United States treaty obligations require any measure of control over a substance, Section 201(d) relieves the Attorney General of his duty to refer the petition to the Secretary of HEW. Petitioner takes the position that subsection (d) does not obviate the statutory referral requirement, but merely authorizes the Attorney [559 F.2d 739] General to override the Secretary's recommendations to the extent those recommendations conflict with United States treaty commitments.

[Footnote 12] See note 9 supra.

[Footnote 13] The criteria for placement in the various schedules are enumerated in 21 U.S.C. § 812(b).

II. THE SINGLE CONVENTION ON NARCOTIC DRUGS

In 1948, in order to simplify existing treaties and international administrative machinery, members of the United Nations undertook codification of a single convention on international narcotics control. [Footnote 14] In 1961, after three preliminary drafts, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs was opened for signature. The United States ratified the Single Convention in 1967 - three years prior to enactment of the Controlled Substances Act.

[Footnote 14] For a history of the Single Convention and its predecessor treaties, see Cohrrsen & Hoover, supra note 2, at 81-87; Lande, The International Drug Control System, reprinted in NATIONAL COMMISSION ON MARIHUANA AND DRUG ABUSE, SECOND REPORT, DRUG USE IN AMERICA: PROBLEM IN PERSPECTIVE, Vol. III, at 11-35 (1973); Lande, The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, 16 INT'L ORG. 776 (1962).

Like the CSA, the Single Convention establishes several classifications or "schedules" of substances, to which varying regimes of control attach. [Footnote 15] Schedule I of the Single Convention contains substances considered to carry a relatively high abuse liability; included in this category are heroin, methadone, opium, coca leaf, and cocaine. [Footnote 16] Schedules II and III contain those substances regarded as less susceptible to abuse. [Footnote 17] Finally, Schedule IV of the Single Convention - unlike CSA Schedule IV - embraces certain Schedule I substances, such as heroin, the abuse liability of which is not offset by substantial therapeutic advantages. [Footnote 18]

[Footnote 15] Article 2 contains a summary of the control provisions applicable to each schedule. The substances contained in each schedule are listed in the appendix to the treaty.

[Footnote 16] See Cohrrsen & Hoover, supra note 2, at 94; Lande, The International Drug Control System, supra note 14, at 96.

[Footnote 17] Drugs contained in Schedule II are also more widely used in medicine than are drugs contained in Schedule I. Lande, The International Drug Control System, supra note 14, at 62-63. Schedule III contains only preparations of narcotic drugs. Ordinarily, preparations are listed in the same Schedule (I or II) that embraces the drug they contain; Schedule III preparations are separately listed because they have no abuse liability and the drugs they contain cannot be recovered by readily applicable means. Id. at 53, 62-63, 94-95, 96-97.

[Footnote 18] See Cohrrsen & Hoover, supra note 2, at 95; Lande, The International Drug Control System, supra note 14, at 21, 97.

In contrast to the CSA, [Footnote 19] the Single Convention prescribes different controls for various parts of the cannabis plant, as defined in Article 1, ¶ 1:

(b) "Cannabis" means the flowering or fruiting tops of the cannabis plant (excluding the seeds and leaves when not accompanied by the tops) from which the resin has not been

extracted, by whatever name they may be designated.

(c) "Cannabis plant" means any plant of the genus cannabis.

(d) "Cannabis resin" means the separated resin, whether crude or purified, obtained from the cannabis plant.

"Cannabis" and "cannabis resin" are listed in Schedules I and IV of the Single Convention and thus are subject to the controls applicable to each of those classifications. As Schedule I drugs [Footnote 20] cannabis and cannabis resin carry the following restrictions: [Footnote 21] Parties to the Single Convention are required to limit production, distribution, and possession of the drugs to authorized medical and scientific purposes. [Footnote 22] Parties must [559 F.2d 740] license and control all persons engaged in manufacture [Footnote 23] or distribution [Footnote 24] of the drugs and must prepare detailed estimates of national drug requirements [Footnote 25] and specified statistical returns. [Footnote 26] Parties may not permit possession of the drugs "except under legal authority." [Footnote 27] Finally, the treaty directs the parties to impose certain penal sanctions. [Footnote 28]

[Footnote 19] For the CSA's definition of "marihuana" see note 7 supra.

[Footnote 20] Article 1, ¶ 1(j) defines "drug" as "any of the substances in Schedules I and II * * *."

[Footnote 21] See generally Art. 2, ¶ 1. The Schedule I control regime is described in Cohrrsen & Hoover, supra note 2, at 95-96. Schedule II drugs are subject to many of the same controls, but carry fewer restrictions on retail trade and no medical prescription requirement. Id. at 96.

[Footnote 22] Art. 4, ¶ (c).

[Footnote 23] Art. 29.

[Footnote 24] Art. 30.

[Footnote 25] Art. 19.

[Footnote 26] Art. 20.

[Footnote 27] Art. 33. This limitation applies whether the drugs are held for distribution or for personal consumption. See Lande, The International Drug Control System, supra note 14, at 59.

[Footnote 28] Art. 36(1) provides:

Subject to its constitutional limitations, each Party shall adopt such measures as will ensure that cultivation, production, manufacture, extraction,

preparation, possession, offering, offering for sale, distribution, purchase sale, delivery on any terms whatsoever, brokerage, dispatch, dispatch in transit, transport, importation

and exportation of drugs contrary to the provisions of this Convention, and any other action which in the opinion of such Party may be contrary to the provisions of this Convention,

shall be punishable offences when committed intentionally, and that serious offences shall be liable to adequate punishment particularly by imprisonment or other penalties of

deprivation of liberty.

Cannabis and cannabis resin and other substances listed in Schedule IV invoke additional restrictions, set forth in Art. 2, ¶ 5:

(a) A Party shall adopt any special measures of control which in its opinion are necessary having regard to the particularly dangerous properties of a drug so included; and

(b) A Party shall, if in its opinion the prevailing conditions in its country render it the most appropriate means of protecting the public health and welfare, prohibit the production,

manufacture, export and import of, trade in, possession or use of any such drug except for amounts which may be necessary for medical and scientific research only, including clinical

trials therewith to be conducted under or subject to the direct supervision and control of the Party. [Footnote 29]

[Footnote 29] In addition to the controls specified for Schedule I and IV substances, Articles 28 and 23 enumerate special measures relating to control of cannabis and cannabis resin. These Articles provide that if a country allows cultivation of the cannabis plant for production of cannabis or cannabis resin - and the United States does so for research purposes - it must establish a national cannabis agency to control such cultivation. The agency must license cultivators, designate areas in which cultivation is permitted, and, after harvesting, take possession of the cannabis crop.

As a result of the treaty's definition of "cannabis," the controls applicable to cannabis and cannabis resin apply to the leaves and seeds of the cannabis plant when they accompany the " flowering or fruiting tops" of the plant. However, when separated from the tops the leaves and seeds do not fall within the definition of "cannabis" or "cannabis resin" and are not subject to the controls applicable to Schedule I or IV substances. [Footnote 30] Art. 28, ¶ 3 is the only provision that applies to separated leaves:

The Parties shall adopt such measures as may be necessary to prevent the misuse of, and illicit traffic in, the leaves of the cannabis plant.

The only provision arguably relevant to cannabis seeds is Art. 2, ¶ 8, which provides:

The Parties shall use their best endeavors to apply to substances which do not fall under this Convention, but which may be used in the illicit manufacture of drugs, such measures of supervision as may be practicable. [Footnote 31]

[Footnote 30] For the sake of convenience, leaves and seeds not accompanying the flowering or fruiting tops will be referred to as "separated" leaves and seeds.

[Footnote 31] Under the definition provided in Art. 1, ¶ 1(n), the term "manufacture" appears to encompass "cultivation."

[559 F.2d 741] III. HISTORY OF THE LITIGATION

A. The first court case.

On May 18, 1972 petitioner NORML and two other interested parties [Footnote 32] petitioned the Director of the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD) to initiate proceedings to remove marihuana from control under the CSA or, alternatively, to transfer the substance from Schedule I to Schedule V. On September 1, 1972 the Director, as delegee of the Attorney General, [Footnote 33] refused to accept the petition for filing. 37 FED. REG. 18097 (1972). He stated that decontrol or reclassification of marihuana would violate United States treaty obligations under the Single Convention. He concluded that Section 201(d), 21 U.S.C. § 811(d), gave him sole authority over the scheduling of substances controlled by treaty, without regard to the referral and rulemaking procedures specified in Section 201(a)-(c). Id. at 18098.

[Footnote 32] Institute for the Study of Health and Society and American Public Health Association. Administrative Law Judge's Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, and Recommended Decision, petitioner's Appendix C at 1.

[Footnote 33] Section 501(a) of the CSA, 21 U.S.C. § 871(a), authorizes the Attorney General to "delegate any of his functions under this subchapter to any officer or employee of the Department of Justice."

NORML filed a petition for review with this court and, on January 15, 1974, the court reversed and remanded for consideration on the merits. National Organization for Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) v. Ingersoll, 162 U.S. App. D.C. 67, 497 F.2d 654 (1974). The court's opinion inveighed against an agency's outright rejection of the filing of a petition, except in narrowly circumscribed situations:

In this case there is no procedural defect or failure to comply with a clear-cut requirement of law. What accounted for respondent's action is his conclusion on the merits that the petition sought action inconsistent with treaty commitment. * * * That kind of determination should have been reflected in an action denying the petition on the merits * * *. * * *

Id. at 659.

In delineating the areas of interest to be addressed on remand, the court indicated that, in view of the treaty's exclusion of separated leaves from the terms "cannabis" and "cannabis resin," the agency should separately consider rescheduling the leaves of the marihuana plant. Id. at 660. [Footnote 34] In addition, the court suggested that the proceeding on remand be divided into two phases:

In the first phase, the Department of Justice could consider whether there is any latitude [to reschedule] consistent with treaty obligations, and herein receive expert testimony limited to this treaty issue. The second phase would arise only if some latitude were found, and would consider how the pertinent executive discretion should be exercised.

Id. at 661 n.17. In connection with this "second phase" the court commented on the Director's argument that under Section 201(d) scheduling of marihuana was a matter entrusted to his sole discretion as delegee of the Attorney General:

This is a matter that gives us pause. The respondent seems to be saying that even though the treaty does not require more control than Schedule V provides, he can on his own say-so and without any reason insist on schedule I. We doubt that this was the intent of Congress.

Id. at 660-661. [Footnote 35]

[Footnote 34] Although NORML's petition to reschedule "marihuana" did not specifically request that the agency consider rescheduling the separated leaves of the plant, the court concluded that the petition should be construed as seeking, alternatively, more limited forms of relief. 497 F.2d at 659, 660.

[Footnote 35] The court added:

The matter is not one on which the expertise of respondent is exclusive, and it would seem appropriate for the court to have the benefit of the

views of sources in the State Department and the international organizations involved. * * *

Id. at 661 (footnote omitted). See note 42 infra.

B. The proceedings on remand.

On June 26, 1974 DEA published a notice in the Federal Register announcing that the [559 F.2d 742] agency was prepared to hold a hearing to determine the regulatory controls necessary to satisfy the Single Convention. 39 FED. REG. 23072 (1974). In response to this notice NORML and the American Public Health Association requested a "phase one" hearing on this issue. They specifically asked that the hearing include an inquiry as to whether separated leaves and/or seeds of the marihuana plant could be removed from CSA Schedule I.

From January 28 through January 30, 1975 a hearing was held before Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) Parker. NORML called two witnesses, Mr. Lawrence Hoover and Dr. Joel Fort, both of whom qualified as experts on the obligations imposed by the Single Convention. Respondent called two chemists, Mr. Philip Porto and Dr. Carlton Turner, as well as DEA's Chief Counsel, Mr. Donald Miller, who qualified as an expert on the treaty issue. [Footnote 36] The parties introduced numerous exhibits.

[Footnote 36] The witnesses' qualifications are discussed at length on pp. 5-6 of the ALJ's Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, and Recommended Decision, reproduced as petitioner's Appendix C. See also 40 FED. REG. 44164 (1975).

On May 21, 1975 ALJ Parker issued his report. Petitioner's Appendix C. He held that, consistent with the Single Convention, "cannabis" and "cannabis resin" - as defined by the treaty - could be rescheduled to CSA Schedule II, cannabis leaves could be rescheduled to CSA Schedule V, and cannabis seeds and "synthetic cannabis" [Footnote 37] could be decontrolled. He rejected respondent's interpretation of Section 201(d) and held that in the second phase of the rescheduling proceeding the agency should follow the referral and hearing procedures set forth in Section 201(a)-(c). Petitioner's Appendix C at 31-34.

[Footnote 37] In reviewing the ALJ's decision, the Acting Administrator of DEA found that "'artificial cannabis' does not exist and what the judge intended is synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol." 40 FED. REG. 44166 (1975).

On appeal from ALJ Parker's order, DEA's Acting Administrator, 38 Henry S. Dogin, denied NORML's petition for rescheduling "in all respects." 40 FED. REG. 44164, 44168 (1975). Turning first to the issue of United States treaty commitments, he held that cannabis and cannabis resin could be rescheduled to CSA Schedule II, separated cannabis leaves could be rescheduled to CSA Schedule III or IV, [Footnote 39] synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol (or THC) and seeds incapable of germination need not be controlled, but seeds capable of germination could not be decontrolled. Id. at 44167-44168. He failed to specify the schedule that would satisfy the Single Convention with respect to seeds capable of germination. [Footnote 40] He did hold, however, that neither cannabis seeds incapable of germination nor synthetic THC were at issue in the proceeding. Id. at 44167, 44168.

[Footnote 38] The functions vested in the Attorney General by the CSA have been delegated to DEA's Acting Administrator pursuant to 28 C.F.R. §§ 0.100 & 0.132(d) (1976).

[Footnote 39] The publication in the Federal Register erroneously states that placement in CSA Schedules III or IV will satisfy treaty requirements relating to "leaves which are capable of germination." 40 FED. REG. at 44168. On Sept. 30, 1975 the Federal Register published a correction, changing the reference to "leaves which are entirely detached from the tops and seeds." Id. at 44856.

[Footnote 40] He did imply that, although Schedule V theoretically would be sufficient, practical problems of law enforcement required more stringent controls. Id. at 44167; see note 84 infra.

After outlining the latitude within which various parts of the marihuana plant could be rescheduled, the Acting Administrator proceeded to determine how to exercise his discretion to reschedule. He examined a letter of April 14, 1975 from Dr. Theodore Cooper, Acting Assistant Secretary for Health. The letter, which was introduced at oral argument before ALJ Parker, states that there "is currently no accepted medical use of marihuana in the United States" and that there "is no approved New Drug Application" for marihuana on file with the [559 F.2d 743] Food and Drug Administration of HEW. [Footnote 41] Relying on this letter, the Acting Administrator concluded that marihuana could not be removed from CSA Schedule I. He stated that Schedule I "is the only schedule reserved for drugs without a currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States." Id. at 44167. Because the letter from Dr. Cooper established that marihuana has no medical use, "no matter the weight of the scientific or medical evidence which petitioners might adduce, the Attorney General could not remove marihuana from Schedule I." Id.

[Footnote 41] The letter, reproduced at 40 FED. REG. 44165 (1975), reads in full:

APRIL 14, 1975

JERRY N. JENSON.

Acting Deputy Administrator, Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Justice, 1405 I Street NW., Washington, D.C. 20537.

DEAR MR. JENSON: At your request, we have prepared the following statement giving our position on the medical uses of Cannabis sativa L. (marihuana).

There is currently no accepted medical use of marihuana in the United States. There is no approved New Drug Application for Cannabis sativa L. (Marihuana) or tetrahydrocannabinol,

the active principle in marihuana. There are Investigational New Drug Applications on file to determine possible therapeutic uses and potential toxic effects of the substance.

We have included for your information a copy of the most recent report on these studies and a copy of the FDA policy regarding clinical studies with marihuana.

Sincerely yours,

THEODORE COOPER, M.D.,

Acting Assistant Secretary for Health.

The implications of the lack of a New Drug Application are discussed more fully in note 65 infra.

Turning finally to the controversy over the interpretation of Section 201(d), the Acting Administrator stated:

It is unnecessary to decide whether Section 201(d) requires the Attorney General to seek the views of HEW on a substance included in an international treaty. In the instance of marihuana he has done so and he has received a reply.

Id. at 44165. [Footnote 42]

[Footnote 42] He also concluded that DEA satisfied the court's suggestion that the agency seek the views of "the international organizations involved." NORML v. Ingersoll, supra note 1, 497 F.2d at 661. In so concluding, he relied on several United Nations documents dealing with the medical and social aspects of marihuana use. See 40 FED. REG. at 44164, 44166, 44168. None of these documents addresses the degree to which various parts of the cannabis plant could be rescheduled in conformity with the Single Convention.

C. The present lawsuit.

On October 22, 1975 NORML filed with this court a petition for review of the Acting Administrator's order. Petitioner urges the court to reverse and remand the case for further proceedings - to include referral of the rescheduling petition to the Secretary of HEW pursuant to Section 201(b)-(c) of the CSA. NORML agrees with ALJ Parker's conclusions as to the scheduling options left open by the Single Convention, except to the extent that he ruled out rescheduling cannabis and cannabis resin below CSA Schedule II. [Footnote 43]

[Footnote 43] Although NORML concedes that the control regimes applicable to the lower schedules would not satisfy the demands of the Single Convention, petitioner's br. at 30, 35, it argues that DEA is authorized to reschedule these two materials below Schedule II and, through the agency's rulemaking powers, to impose additional controls commensurate with United States treaty obligations.

Respondent proffers alternative arguments in defense of the Acting Administrator's decision to deny NORML's rescheduling petition and thereby perpetuate placement of marihuana in CSA Schedule I. Respondent alleges first that by virtue of Section 201(d) the referral and hearing procedures of Section 201(a)-(c) do not apply to drugs subject by treaty to international control. Accordingly, the decision whether to reschedule marihuana is entrusted to the Acting Administrator, as delegee of the Attorney General, and the only question open on review is whether his decision not to reschedule the drug is based on substantial evidence. Section 507, 21 U.S.C. § 877. [Footnote 44] [559 F.2d 744] Alternatively, respondent suggests that the Acting Administrator satisfied the referral and hearing requirements by basing his rescheduling decision on the letter from Dr. Cooper. Finally, although conceding in its brief and at oral argument that filing of a petition to reschedule synthetic THC would "require consideration by DEA," respondent's br. at 18, respondent contends that reclassification of synthetic THC is not an issue in this proceeding.

[Footnote 44] Respondent answers this question in the affirmative, noting in particular Dr. Cooper's statement that marihuana lacks a currently accepted medical use - allegedly a prerequisite for placement in CSA Schedules II through V. Respondent's br. at 6-11, 14-15.

IV. SCHEDULING DECISIONS UNDER SECTION 201

A. Statutory construction of Section 201(d).

We agree with the parties that the Single Convention leaves some degree of latitude within which to reschedule the various parts of the marihuana plant under the CSA. We defer our discussion of the precise degree of that latitude and turn first to the crucial question confronting the court: interpretation of Section 201(d). We note at the outset that the Acting Administrator declined to decide the issue. [Footnote 45]

[Footnote 45] The Acting Administrator strongly intimated that in his view § 201(d) completely displaces the referral and hearing procedures of § 201(a)-(c). See 40 FED. REG. at 44167. However, because he found that under § 201(b)-(c) Dr. Cooper's letter represented adequate input from HEW, the Acting Administrator concluded that it was not necessary to reach the question. Id. at 44165.

Section 201(d) provides that if control of a substance is required by United States treaty obligations, "the Attorney General shall issue an order controlling such drug under the schedule he deems most appropriate to carry out such obligations," without regard to the referral and hearing procedures prescribed by Section 201(a)-(c) and without regard to the Section 202 criteria ordinarily governing scheduling decisions. Each party relies on the language and history of subsection (d) to support its construction of the provision. However, although the report of the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce does make specific reference to Section 201 (d), the statements essentially track the language of the provision and offer little guidance for statutory interpretation. [Footnote 46] Nevertheless, [559 F.2d 745] the events surrounding the drafting of Section 201(a)-(d) reveal an overarching congressional aim to limit the Attorney General's authority to make scheduling judgments under the Act - a goal that militates strongly in favor of petitioner's interpretation of Section 201(d).

[Footnote 46] The House report contains two unilluminating allusions to § 201(d). First, after briefly discussing the requirements of § 201(a)-(c), the report notes:

An exception [to the § 201(a)-(c) rescheduling procedures] is made in the case of treaty obligations of the United States. If a drug is required to

be controlled pursuant to an international treaty, convention, or protocol in effect on the enactment of the bill, the drug will be controlled in conformity with the treaty or other

international agreement obligations.

H.R. Rep. No. 91-1444, 91st Cong., 2d Sess., pt. 1, at 4 (1970). Later the report states:

Under subsection (d), where control of a drug or other substance by the United States is required by reason of its obligations under an international

treaty, convention, or protocol which is in effect on the effective date of part B of the bill (i.e., the date of its enactment), the bill does not require that the Attorney General

seek an evaluation and recommendation by the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, or pursue the procedures for control prescribed by the bill but he may include the drug or other

substance under any of the five schedules of the bill which he considers most appropriate to carry out the obligations of the United States under the international instrument, and he may

do so without making the specific findings otherwise required for inclusion of a drug or other substance in that schedule. The reference to treaties, conventions, or protocols in effect

upon enactment of the bill is intended to refer to the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, and to those predecessor conventions or protocols as to which the United States may still

have an obligation. This would include any obligations of the United States that might arise after enactment of the bill by reason of changes in the schedules of the Single Convention by

the international organs specified in the convention under the authority of the provisions of the convention in effect as to the United States on the date of enactment of the

bill.

Id. at 36.

The Senate bill, S. 3246, lacked a provision for binding recommendations by HEW and did not contain a counterpart to § 201(d). Consequently, the report of the Senate Committee on

the Judiciary, S. Rep. No. 91-613, 91st Cong., 1st Sess. (1969), is even less helpful.

Following extensive debate on the Senate floor, proposals to transfer much of the Attorney General's scheduling authority to the Secretary of HEW were narrowly defeated. [Footnote 47] However, the bill reported and passed in the House of Representatives incorporated the philosophy of the defeated Senate amendments: The bill required the Attorney General, in making scheduling decisions, to request from the Secretary of HEW his scientific and medical evaluation of the need for control; unlike the Senate bill, the House bill made his recommendations binding on the Attorney General. [Footnote 48] This division of decisionmaking responsibility was fashioned in recognition of the two agencies' respective areas of expertise. Members of the House repeatedly stated that the Department of Justice should make judgments based on law enforcement considerations, while HEW should have the [559 F.2d 746] final say with respect to medical and scientific determinations. [Footnote 49] After minor revisions in conference, [Footnote 50] the House version of the bill was signed into law as the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. [Footnote 51]

[Footnote 47] Even before consideration by the full Senate, the bill provoked substantial controversy in committee. The Senate report states:

This title vests the authority for control of the substances enumerated under its provisions with the Attorney General.

There has been a point of controversy evident among the professions involved in drug control and drug research on whether or not the Justice Department has the expertise to

schedule or reschedule drugs since such decisions require special medical knowledge and training.

This difficulty is resolved by the provision contained in this title which requires the Attorney General to seek advice from the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare

and from the Scientific Advisory Committee on whether or not a substance should be added, deleted or rescheduled with respect to the provisions of the bill.

S. Rep. No. 91-613, supra note 46, at 5.

After the bill was reported, Senator Hughes of Iowa introduced several amendments designed to limit the Attorney General's scheduling responsibilities. Senator Hughes initially

proposed that HEW be given almost total responsibility over such decisions:

Although [the Attorney General] does have, and should have, the right of research and development in the areas that are related directly to law

enforcement, it would be better to leave the determining of dangerous substances and changing in schedules of classification up to the Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare.

116 CONG REC. 1333 (1970); see id. at 974.

In resisting the "effort to shift [scheduling] power from the Attorney General to the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare," id. at 1330 (remarks of

Sen. Hruska), the bill's sponsors, Senators Dodd and Hruska, asserted that the bill ensured adequate interplay between the Department of Justice and HEW. Specifically, they

insisted that a provision requiring the Attorney General to seek nonbinding "advice" from HEW met any objections regarding the Attorney General's lack of expertise

in science and medicine. See id. at 975 (remarks of Sen. Hruska), 977, 978, 996, 1329 (remarks of Sen. Dodd). The Hughes amendment was defeated 46 to 36, with 18 not

voting. Id. at 1335.

Thereafter, Senator Hughes introduced a more modest amendment to increase HEW's role in scheduling decisions. He proposed that addition, deletion, or rescheduling of a substance

could be effected by the Attorney General only upon recommendation of the Secretary of HEW (or a specially created "Scientific Advisory Committee"). Id. at 1641,

1642. He explained:

The provisions of this amendment do not make radical changes in the bill as reported. They do not transfer, as many have urged, the responsibility

for such scientific determinations from the Department of Justice to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. All that they require is that in making decisions on essentially

scientific and medical questions, the Attorney General act on the basis of recommendations from those agencies of the Government best qualified to make an expert judgment on the

questions involved.

Id. at 1642.

The sponsors of the bill again opposed the Hughes proposal. See id. at 1642-1646 (remarks of Sens. Dodd & Hruska). The amendment lost by a narrower margin, 44 to

39. Id. at 1647.

[Footnote 48] H.R. Rep. No. 91-1444, supra note 46, pt. 1, at 4, 32-33; 116 CONG REC. 33606-33607 (1970) (reproducing § 201 of the House bill, H.R. 18583); see

id. at 33297 (remarks of Rep. Madden), 33300 (remarks of Rep. Springer), 33304, 33305 (remarks of Rep. Rogers), 33308 (remarks of Rep. Carter), 33316 (remarks of Rep.

Boland), 33651 (remarks of Rep. Brotzman), 33658 (remarks of Rep. Cohelan).

Except for cross-references contained therein, § 201(a)-(c) of H.R. 18583 as passed by the House is identical to § 201(a)-(c) of the CSA as enacted.

[Footnote 49] Representative Springer, one of the sponsors of H.R. 18583, remarked:

Let us also make a definite point of the fact that purely enforcement responsibilities are placed with the Department of Justice while medical and

scientific judgments necessary to drug control are left where they properly should lie and that is with the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

116 CONG. REC. 33300 (1970). Another sponsor, Representative Carter, echoed these sentiments:

Representatives of the medical and scientific community also expressed doubts regarding the Attorney General's authority to make final decisions on

which drugs should be controlled. Again, this concern was taken care of by language which requires the Attorney General to seek advice of the Secretary of Health, Education, and

Welfare on drug control questions, and which makes the Secretary's advice with respect to medical and scientific issues binding on the Attorney General. In this way, an appropriate

balance was achieved between scientific interest[s] and those of law enforcement.

Id. at 33308. Various other comments make clear that there existed in the House a consensus that "considering that the scheduling of a substance is based largely

on scientific information, it seems most inappropriate that law-enforcement authorities should have the last word on the content of the schedules." Id. at 33316

(remarks of Rep. Boland); see id. at 33304 (remarks of Rep. Rogers).

[Footnote 50] See H.R. Rep. No. 91-1603, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970) (conference report).

[Footnote 51] Pub. L. No. 91-513, 84 STAT. 1242 (codified at 21 U.S.C. § 801 et seq.).

Section 201(d) must be read against this backdrop of intense concern with establishing and preserving HEW's avenue of input into scheduling decisions. Comments by various congressmen confirm the limited purpose of subsection (d): to authorize the Attorney General to disregard scheduling criteria and HEW recommendations that would otherwise lead to scheduling of a substance in violation of treaty commitments. [Footnote 52] Congress never intended to allow the Attorney General to displace the Secretary whenever any international obligations attach to a particular drug - especially in view of the fact that the vast majority of substances listed in the CSA are controlled by treaty. [Footnote 53] Respondent's reading of Section 201(d) would destroy a balance of power created by a deliberate and conscientious exercise of the legislative process.

[Footnote 52] Remarks on the House floor reveal that international requirements qualify, but do not displace, the usual referral and hearing procedures. One qualification was described by Representative Hastings, who stated that where control of a drug is required by treaty, "the Attorney General may control the substance and list it in the appropriate schedule, without regard to the findings required by the schedule." 116 CONG. REC. 33309 (1970). Representative Boland described a second qualification: "H.R. 18583 requires, in the absence of international treaty obligations, that the Attorney General follow the advice of the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare on scientific and medical matters and may not control a substance if the Secretary decides it should not be controlled." Id. at 33316. In short, "if a drug is required to be controlled pursuant to an international treaty, convention, or protocol in effect on the enactment of the bill, the drug will be controlled by conformity with the treaty or other international agreement obligations." Id. at 33297 (remarks of Rep. Madden).

[Footnote 53] Indeed, the Single Convention controls almost 90 percent of the 64 nonhallucinogenic substances enumerated in Schedule I of the CSA as originally enacted.

The language of Section 201(d) is consistent with the clear import of the Act's legislative history. The section provides that the Attorney General shall, without regard to the usual referral and hearing procedures, "issue an order controlling such drug under the schedule he deems most appropriate to carry out such [international] obligations * * *." (Emphasis added.) The underscored phrase, which is omitted from the dissent's discussion of this section, circumscribes the Attorney General's scheduling authority: it enables him to place a substance in a CSA schedule - without regard to medical and scientific findings - only to the extent that placement in that schedule is necessary to satisfy United States international obligations. Had the provision been intended to grant him unlimited scheduling discretion with respect to internationally controlled substances, it [559 F.2d 747] would have authorized him to issue an order controlling such drug "under the schedule he deems most appropriate."

Our interpretation of Section 201(d) ensures proper allocation of decisionmaking responsibility between the Attorney General and the Secretary of HEW, in accordance with their respective spheres of expertise. Section 201(d) directs the Attorney General, as an initial matter, to make a legal judgment as to controls necessitated by international commitments. He then establishes a minimum schedule or level of control below which placement of the substance may not fall. Determination of a minimum schedule ensures that the Secretary's recommendation, which ordinarily would be binding as to medical and scientific findings, does not cause a substance to be scheduled in violation of treaty obligations. However, once that minimum schedule is established by the Attorney General, the decision whether to impose controls more restrictive than required by treaty implicates the same medical and scientific considerations as do scheduling decisions regarding those few substances not controlled by treaty. The Secretary of HEW is manifestly more competent to make these nonlegal evaluations and recommendations.

Moreover, we think it not insignificant that the Office of Legal Counsel of the Department of Justice, in a memorandum dated August 21, 1972, [Footnote 54] adopted the following construction of Section 201(d): The Attorney General is directed to determine the CSA schedule that will satisfy the nation's obligation under the Single Convention; to the extent that there is latitude to schedule a substance with treaty obligations, "the Attorney General [is] obliged to follow the prescribed procedures in obtaining a medical and scientific evaluation from the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare." Petitioner's Appendix F at 14. Thus in rejecting DEA's interpretation of Section 201(d), we embrace the same interpretation urged by staff counsel to DEA's parent agency, the Department of Justice. [Footnote 55]

[Footnote 54] The memorandum, entitled "Petition to Decontrol Marihuana, Interpretation of Section 201 of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970," was prepared by Deputy Assistant Attorney General Mary C. Lawton at the request of the Director of BNDD for the Justice Department's legal opinion on the procedures to be followed with respect to the then recently filed NORML petition for rescheduling. DEA supplied the memorandum to NORML in response to a general request for documents.

[Footnote 55] We note too that this court in NORML v. Ingersoll, supra note 1, 497 F.2d at 660-661, expressed its "doubts" that the delegee of the Attorney General could, "without any reason," decide not to reschedule marihuana. We think it insufficient answer to say that the Acting Administrator did not act without reason because he sought out "expert opinion as to treaty and medical questions." Respondent's br. at 9. The statute requires more than an informal canvassing of opinion.

B. Satisfaction of the referral and hearing procedures of Section 201(a)-(c).

As an alternative argument respondent contends - and the Acting Administrator held - that whatever the proper interpretation of Section 201(d), Dr. Cooper's letter satisfied the Section 201(b)-(c) requirement that the Acting Administrator refer the petition to the Secretary of HEW for medical and scientific findings and recommendations. The Acting Administrator premised his conclusion on the assumption that placement in CSA Schedule I is automatically required if the substance has no currently accepted medical use in the United States. Our analysis of the Act compels us to reject his finding.

The CSA makes clear that, upon referral by the Attorney General, the Secretary of HEW is required to consider a number of different factors in making his evaluations and recommendations. Section 201(b)-(c) specifies that the Secretary must consider "scientific evidence of [the substance's] pharmacological effect, if known"; "the state of current scientific knowledge regarding the drug or other substance"; "what, if any, risk there is to the public health"; the drug's "psychic or physiological dependence liability"; "whether the substance is an immediate precursor of a substance already controlled under this subchapter"; and any scientific or medical factors [559 F.2d 748] relating to the drug's "actual or relative potential for abuse," its "history and urrent pattern of abuse," and "scope, duration, and significance of abuse." The provision does not in any way qualify the Secretary's duty of evaluation. [Footnote 56] If, as respondent contends, a determination that the substance has no accepted medical use ends the inquiry, then presumably Congress would have spelled that out in its procedural guidelines. Its failure to do so indicates an intent to reserve to HEW a finely tuned balancing process involving several medical and scientific considerations. By shortcutting the referral procedures of Section 201(b)-(c) the Acting Administrator precluded the balancing process contemplated by Congress.

[Footnote 56] Indeed, the House report specifically states: "Aside from the criterion of actual or relative potential for abuse, subsection (c) of section 201 lists seven other criteria * * * which must be considered in determining whether a substance meets the specific requirements specified in section 202(b) for inclusion in particular schedules * * *." H.R. Rep. No. 91-1444, supra note 46, pt. 1, at 35 (emphasis added).

Admittedly, Section 202(b), 21 U.S.C. § 812(b), which sets forth the criteria for placement in each of the five CSA schedules, established medical use as the factor that distinguishes substances in Schedule II from those in Schedule I. However, placement in Schedule I does not appear to flow inevitably from lack of a currently accepted medical use. Like that of Section 201(c), the structure of Section 202(b) contemplates balancing of medical usefulness along with several other considerations, including potential for abuse and danger of dependence. [Footnote 57] To treat medical use as the controlling factor in classification decisions is to render irrelevant the other "findings" required by Section 202(b). The legislative history of the CSA indicates that medical use is but one factor to be considered, and by no means the most important one. [Footnote 58]

[Footnote 57] See note 56 supra. In United States v. Maiden, 355 F. Supp. 743, 748-749 n.4 (D. Conn. 1973), Judge Newman acknowledged that the scheduling criteria

of § 202 cannot, in all situations, be strictly applied:

Section 202 of the Act, in establishing the three findings for each of the five schedules, does not in terms specify whether the findings are

cumulative. * * * In fact they cannot logically be read as cumulative in all situations. For example finding (B) for Schedule I requires that "The drug or other substance has

no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States." Finding (B) for the other four schedules specifies that the drug has a currently accepted medical use. At

the same time, finding (A) requires that the drug has a "high potential for abuse" for placement in Schedule I, but a "potential for abuse less than the drugs or other

substances in schedules I and II" for placement in Schedule III. If the findings are really cumulative, where would one place a drug that has no accepted medical use but also has

a potential for abuse less than the drugs in Schedules I and II? * * *

Judge Newman concluded that one way to reconcile this inconsistency is to assume that "applicability of finding (B) concerning currently accepted medical use should be made first.

If the drug has none (and marijuana probably does not, though the testimony indicated some interesting potential uses), then placement in Schedule I may be appropriate whether or not

the potential for abuse is higher than for other drugs * * *." Id. As a logical proposition, this conclusion is not unsound. However, the legislative history of the CSA

and the present case indicate that medical use should not be regarded as the critical factor.

[Footnote 58] See, e.g., H.R. Rep. No. 91-1444, supra note 46, pt. 1, at 34 ("[a] key criterion for controlling a substance * * * is the substance's potential for abuse"). See also Vodra, supra note 5, at 37.

Moreover, DEA's own scheduling practices support the conclusion that substances lacking medical usefulness need not always be placed in Schedule I. At the hearing before ALJ Parker DEA's Chief Counsel, Donald Miller, testified that several substances listed in CSA Schedule II, including poppy straw, have no currently accepted medical use. Tr. at 473-474, 488. He further acknowledged that marihuana could be rescheduled to Schedule II without a currently accepted medical use. Tr. at 487-488. Neither party offered any contrary evidence.

More importantly, even if lack of medical use is dispositive of a classification [559 F.2d 749] decision, we do not think the finding in this case was established in conformity with the statute. Dr. Cooper's letter is addressed to a member of DEA's legal staff, in response to the latter's inquiry; the letter was not solicited by the Acting Administrator, and it can hardly take the place of the elaborate referral machinery contemplated by Congress. [Footnote 59] The one page letter makes conclusory statements without providing a basis for or explanation of its findings. [Footnote 60] It is unclear what Dr. Cooper means when he writes that marihuana has no currently accepted medical use. As a legal conclusion, his statement cannot be doubted: Placement in Schedule I creates a self-fulfilling prophecy, Tr. at 170, because the drug can be used only for research purposes, Tr. at 488, and therefore is barred from general medical use. But if Dr. Cooper's statement is meant to reflect a scientific judgment as to the medicinal potential of marihuana, then the basis for his evaluation should be elaborated. Recent studies have yielded findings to the contrary: [Footnote 61] HEW's Fifth Annual Report to the U.S. Congress, Marihuana and Health (1975), devotes a chapter to the therapeutic aspects of marihuana, discovered through medical research. Id. ch. 9, at 117-127. Possible uses of marihuana include treatment of glaucoma, [Footnote 62] asthma, and epilepsy, and provision of "needed relief for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy." Id. at 117. These promising findings were discussed by Dr. Fort in his testimony before ALJ Parker. Tr. at 163-165, 169-170. Only a formal referral and hearing will allow due weight to be given to such findings. [Footnote 63] Accordingly, recognizing that it is our obligation as a court to ensure that the agency acts within statutory bounds, [Footnote 64] we hold that Dr. Cooper's [559 F.2d 750] letter was not an adequate substitute for the procedures enumerated in Section 210(a)-(c). [Footnote 65] The case must be remanded for further proceedings consistent with those statutory requirements.

[Footnote 59] For a detailed description of the steps taken by HEW after referral by the Attorney General, see Vodra, supra note 5, at 34:

Once DEA has collected the "necessary data," the Administrator of DEA (by authority of the Attorney General) requests from HEW a

"scientific and medical evaluation" and recommendations as to whether the drug or other substance should be controlled or removed from control. This request is filed

with the Commissioner of FDA, who has the responsibility for coordination of activities within HEW. The Commissioner solicits evaluations and recommendations from the affected

bureaus within FDA (e.g., Bureau of Drugs, Bureau of Veterinary Medicine), from the National Institute of Drug Abuse, and from the Controlled Substances Advisory Committee. There

is no statutory requirement that HEW receive comments from, or provide a hearing to, interested parties in preparing its evaluation and recommendations. A reason for creating this

advisory committee, however, is to provide a forum whereby HEW can hear from interested persons, the medical and scientific community, and the public. Once these evaluations are

received, the Commissioner submits a report and recommendations to the Assistant Secretary for Health. The Assistant Secretary (by authority of the Secretary) then transmits back

to DEA his medical and scientific evaluation regarding the substance and his recommendations as to whether the drug should be controlled.

(Footnotes omitted.)

[Footnote 60] Because the letter was not introduced until oral argument before ALJ Parker, petitioner did not have opportunity to probe into these matters at the evidentiary hearing.

[Footnote 61] See United States v. Randall, Crim. No. 65923-75 (D.C. Super. Ct., Nov. 24, 1976), reprinted in 104 DAILY WASH. L. REPTR 2249, 2252 (1976).

[Footnote 62] Indeed, in United States v. Randall, supra note 61, the District of Columbia Superior Court held that a defendant suffering from glaucoma had established a valid defense of medical necessity to a charge of possession of marihuana. Counsel for DEA acknowledged at oral argument that the federal government is presently issuing "investigational" marihuana cigarettes to Randall. See Washington Post, Dec. 12, 1976, at A8, col. 1.

[Footnote 63] DEA does not dispute that a finding of medical usefulness would not violate the Single Convention, which allows signatories leeway in defining medical purposes. Tr. at 52-53, 160, 471-472; see Lande, The International Drug Control System, supra note 14, at 42-50.

[Footnote 64] We are cognizant that deference is owed to any agency decision construing a statute continually applied by the interpreting agency - particularly where the statutory

meaning "is enhanced by technical knowledge * * *." Columbia Gas Transmission Corp. v. FPC, 174 U.S. App. D.C. 204, 530 F.2d 1056, 1059 (1976); see Natural

Resources Defense Council, Inc. v. Train, 166 U.S. App. D.C. 312, 510 F.2d 692, 706 (1974); Bamberger v. Clark, 129 U.S. App. D.C. 70, 390 F.2d 485, 488 (1968). But

the doctrine of deference to agency rulings unquestionably has its limits, and administrative decisions regarding the propriety of agency action stand on a different footing. Courts

must be vigilant to ensure that the agency's procedures and underlying standards are in accord with the law: "Reviewing courts are not obliged to stand aside and rubber-stamp

their affirmance of administrative decisions that they deem inconsistent with a statutory mandate or that frustrate the congressional policy underlying a statute." NLRB v.

Brown, 380 U.S. 278, 291 (1965); see Wheatley v. Adler, 132 U.S. App. D.C. 177, 407 F.2d 307, 310 (1968) (en banc). As this court

explained in its en banc decision in International Brhd of Elec. Wkrs v. NLRB, 159 U.S. App. D.C. 272, 487 F.2d 1143, 1170-1171 (1973), aff'd, sub nom.

Florida Power & Light Co. v. International Brhd of Elec. Wkrs, 417 U.S. 790 (1974) (quoting SEC v. Chenery Corp.,

332 U.S. 194, 215 (1947) (Jackson, J., dissenting)):

"Administrative experience is of weight in judicial review only to this point - it is a persuasive reason for deference to [an agency] in

the exercise of its discretionary powers under and within the law. It cannot be invoked to support action outside of the law. And what action is, and what is not, within the law

must be determined by courts, when authorized to review, no matter how much deference is due to the agency's fact finding. Surely an administrative agency is not a law unto

itself * * *." * * *

In order to prevent unfair and uninformed decisions on petitions to reschedule substances under the CSA, the Act establishes specific procedures that the agency must follow. By

circumventing those procedures, DEA usurped the powers reserved to HEW and worked a hardship on petitioner. Whatever the Acting Administrator's conclusion, we cannot countenance

actions in derogation of a statutory mandate.

[Footnote 65] Citing Dr. Cooper's letter, respondent further argues that placement in Schedule I is mandated because there is "no approved New Drug Application" for marihuana.

This reference is to the procedure by which persons who wish to ship substances in interstate commerce apply to the Secretary of HEW for approval of a New Drug Application (NDA) under

the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. § 301 et seq. (1970). See 21 U.S.C. § 355. Respondent argues that this procedure establishes whether a substance has

"an accepted safety for use," and concludes that "rescheduling of marihuana would be impossible under the [Controlled Substances] Act without a reappraisal from the

Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare." Respondent's br. at 16.

The interrelationship between the two Acts is far from clear. See generally American Pharmaceutical Ass'n v. Weinberger, 377 F. Supp. 824 (D. D.C. 1974), aff'd,

sub nom. American Pharmaceutical Ass'n v. Mathews, 174 U.S. App. D.C. 202, 530 F.2d 1054 (1976). Nevertheless, it cannot be doubted that "Congress intended to

create two complementary institutional checks on the production and marketing of new drugs." Id. at 830. Respondent provides no reason to suppose Congress intended that

the NDA institutional check necessarily precede the CSA check. Even if NORML were to obtain approval of an NDA for marihuana, it would then have to apply to DEA to reschedule the drug.

Cf. 21 C.F.R. § 1308.21(a) (1976). We think it not inappropriate for NORML to apply first for rescheduling under the CSA.

V. CONTROLS REQUIRED BY THE SINGLE CONVENTION

We turn now to a discussion of the scheduling options left open by the Single Convention.

A. Cannabis and cannabis resin.

The Single Convention defines "cannabis" as the fruiting or flowering tops of the cannabis plant, including leaves when not detached, Art. 1, ¶ 1(b), and "cannabis resin" as any resin that has been extracted from the plant. Art. 1, ¶ 1(d). These "drugs" are listed in Schedules I and IV of the treaty and are therefore subject to severe restrictions on manufacturing, distribution, and international trade. [Footnote 66] Nevertheless, the parties agree and the Acting [559 F.2d 751] Administrator held [Footnote 67] that cannabis and cannabis resin could be rescheduled to CSA Schedule II consistent with the Single Convention. [Footnote 68]

[Footnote 66] See text accompanying notes 21-28 supra.

[Footnote 67] 40 FED. REG. 44167-44168 (1975).

[Footnote 68] The Acting Administrator also noted, id. at 44166, that the Department of State, in a letter published earlier in the Federal Register, 39 FED. REG. 23072-23075 (1974), took the position that, pursuant to the Single Convention, cannabis tops and cannabis resin must be placed in CSA Schedule I or II.

Comparison of the control regimes of the CSA and the Single Convention reveals the rationality of this consensus. The primary difference between substances in CSA Schedule I and those in Schedule II is that the former may be used for research only, whereas the latter may be prescribed by licensed physicians. Tr. at 488. [Footnote 69] Nothing in the Single Convention requires that cannabis and cannabis resin be limited to research. In Art. 2, ¶ 5 the treaty provides several open-ended guidelines applicable to Schedule IV drugs such as cannabis and cannabis resin. For example, a nation must limit production of, trade in, and use of a Schedule IV substance for research purposes "if in its opinion the prevailing conditions in its country render it the most appropriate means of protecting the public health and welfare * * *." Art. 2, ¶ 5(b). In a similar vein, Art. 2, ¶ 5(a) provides that a nation must "adopt any special measures of control which in its opinion are necessary having regard to the particularly dangerous properties of a drug so included * * *." The official interpretation of the Single Convention, Commentary on the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961 ("Commentary"), prepared by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, states that the only requirement imposed by these provisions is that the party act in good faith in determining whether any special measures are needed with regard to Schedule IV drugs. Petitioner's Appendix E at 65. ALJ Parker correctly held that under this standard the United States could decline to restrict cannabis and cannabis resin to research purposes and could reschedule the drugs to CSA Schedule II. [Footnote 70] Neither respondent nor the Acting Administrator contests this conclusion.

[Footnote 69] Section 309, 21 U.S.C. § 829, specifies conditions under which substances in CSA Schedules II, III, and IV may be prescribed. Schedule V drugs may be dispensed without a prescription.

[Footnote 70] See note 63 supra. New studies have indicated that the dangers of marihuana use are not as great as once believed. A recent report of a federal panel representing, inter alia, HEW, DEA, the State Department, and the White House, concluded that marihuana use entails a "relatively low social cost," and suggested that decriminalization be considered. Washington Post, Dec. 12, 1976, at A1, col. 1; Washington Star, Dec. 12, 1976, at A7, col. 1. See United States v. Randall, supra note 61, at 2254 (characterizing marihuana as "a drug with no demonstrably harmful effects"). Indeed, in NATIONAL COMMISSION ON MARIHUANA AND DRUG ABUSE, SECOND REPORT, DRUG USE IN AMERICA: PROBLEM IN PERSPECTIVE, Vol. I, at 235 (1973), the Commission recommended that "the United States take the necessary steps to remove cannabis from the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961), since this drug does not pose the same social and public health problems associated with the opiates and coca leaf products."

The parties further agree that, without imposition of additional restrictions on lower schedules, CSA Schedule II is necessary as well as sufficient to satisfy our international obligations. Petitioner's br. at 30, 35; respondent's br. at 12. As detailed in ALJ Parker's Findings, petitioner's Appendix C at 22-24, several requirements imposed by the Single Convention would not be met if cannabis and cannabis resin were placed in CSA Schedule III, IV or V. [Footnote 71] NORML concedes [559 F.2d 752] this point; however, it argues that the delegee of the Attorney General could place the substances in a less restrictive schedule provided he exercised his rulemaking authority to impose additional restrictions to satisfy the Single Convention. [Footnote 72] Petitioner's br. at 35-41. ALJ Parker rejected this argument, expressing some reservations as to whether the Attorney General had the authority to promulgate such rules. Petitioner's Appendix C at 25-26. Respondent agrees with ALJ Parker, adding that "petitioner's request, that DEA create a new schedule for marihuana, is beyond the scope of DEA's authority under the Act." Respondent's br. at 12. The Acting Administrator sidestepped the issue by concluding that a lack of currently accepted medical use mandates that marihuana remain in CSA Schedule I. 40 FED. REG. 44167, 44168 (1975).

[Footnote 71] For example, Art. 31, ¶ 4 requires import and export permits that would not be obtained if the substances were placed in CSA Schedules III through V. See Controlled Substances Import and Export Act, 21 U.S.C. § 951 et seq. (1970). In addition, the quota and recording requirements of Articles 19 through 21 of the Single Convention would be satisfied only by placing the substances in CSA Schedule I or II. Tr. at 422-424. See 21 U.S.C. § 826.

[Footnote 72] The primary benefit of this hybrid classification would be the reduced penalty scheme that applies to violations of controls imposed on substances in CSA Schedules III through V. See 21 U.S.C. §§ 841-843.

This court need not decide whether the Attorney General's rulemaking authority permits creation of a hybrid classification. In the circumstances of this case, Section 201(d) plainly authorizes him to decline to promulgate the rules suggested by petitioner. NORML ignores the language of that section, which directs the Attorney General to issue an order controlling a substance "under the schedule he deems most appropriate to carry out" United States international obligations. Even under a narrow reading of subsection (d), the Attorney General - to satisfy treaty requirements - is directed to establish a minimum schedule below which the substance in question may not be placed. Establishment of this minimum schedule is based on a legal judgment as to the controls mandated by the Single Convention, and need not be justified by medical and scientific findings.

Petitioner's request for special rulemaking undercuts the language and purpose of Section 201(d). If, as NORML suggests, the Attorney General must consider whether a substance controlled by treaty can be placed in a less restrictive CSA schedule provided additional requirements are imposed through the rulemaking process, then Congress would not have authorized him to place the substance in the schedule he deems most appropriate to carry out our treaty obligations. If Section 201(d) is to have any meaning at all, it must be read to authorize placement of cannabis and cannabis resin in CSA Schedule II, despite the fact that a specially imposed combination of controls might meet the requirements of the Single Convention. Congress surely did not intend to require the Attorney General to consider creation of a hybrid schedule each time an interested party files a petition to reschedule a substance controlled by treaty.

B. Cannabis leaves (when unaccompanied by the tops).

NORML contends that ALJ Parker was correct in finding that under the Single Convention cannabis leaves may be rescheduled to CSA Schedule V. Respondent defends the Acting Administrator's conclusion that cannabis leaves may be rescheduled to CSA Schedule III or IV but not to Schedule V. See 40 FED. REG. 44167, 44168 (1975).

As noted earlier, Art. 28, ¶ 3 contains the treaty's only reference to separated cannabis leaves. That provision states that "the Parties shall adopt such measures as may be necessary to prevent the misuse of, and illicit traffic in, the leaves of the cannabis plant." Petitioner's and respondent's expert witnesses both agreed that the treaty leaves to the discretion of each country the determination of measures necessary to prevent misuse and illicit traffic. [Footnote 73] Tr. at 43, 48, 127, 415, 445, 452. ALJ Parker concluded [559 F.2d 753] that "any measures which the United States adopted when, viewed objectively, amounted to a good faith effort to prevent the 'misuse of, and illicit traffic in, the leaves of the cannabis plant' * * * would satisfy our obligations under the Convention." Petitioner's Appendix C at 28. The Acting Administrator added that a good faith effort would have to be "our best effort." 40 FED. REG. 44166 (1975).

[Footnote 73] The Commentary defines "illicit traffic" in this context as "trade in the leaves contrary to domestic legal provision intended to combat their misuse, or to foreign laws governing such trade." Petitioner's Appendix E at 315.

The major difference between substances placed in CSA Schedule IV and those placed in Schedule V is that under Section 309, 21 U.S.C. § 829, the former may be dispensed only by prescription. The Single Convention does not require that cannabis leaves be dispensed only by prescription. [Footnote 74] In fact, the Commentary to the treaty provides:

Parties are not bound to prohibit the consumption of the leaves for non-medical purposes, [Footnote 75] but only to take the necessary measures to prevent their misuse. This might involve an obligation to prevent the consumption of very potent leaves, or of excessive quantities of them. It may be assumed that Parties would in any case not be permitted by paragraph 3 to authorize the uncontrolled use of the leaves. Any authorized consumption would have to be governed by such regulations as would be required to prevent illicit traffic and misuse. [Footnote 76] The conditions under which non-medical consumption might be permitted might also depend on the outcome of the studies which at the time of this writing are being carried out concerning the effects of the use of the leaves.

Petitioner's Appendix E at 316. Moreover, the history of the treaty provision in question indicates that countries are given much leeway in determining what is "misuse of" and "illicit traffic in" cannabis leaves and in fashioning methods of preventing these two evils. [Footnote 77]

[Footnote 74] Art. 30, P 2(b)(i) requires "medical prescriptions for the supply or dispensation of drugs to individuals." However, under the treaty separated cannabis leaves are not listed in Schedule I or II and therefore, pursuant to Art. 1, ¶ 1(j), are not defined as drugs.

[Footnote 75] Art. 4, ¶ (c) requires the parties to limit production, distribution, possession, and use of drugs to medical and scientific purposes. Separated leaves are not "drugs" and therefore are not subject to this restriction.

[Footnote 76] One commentator describes the measures that a party might adopt to prevent misuse of and illicit traffic in the leaves:

The measures required to prevent misuse might include the prohibition of the sale of very potent leaves, of the sale of excessive quantities to one

individual and of the sale to persons below a certain age. These are only a few examples of what parties might have to do under the vague provision of the Convention. The obligation

to prevent the illicit traffic in the leaves may be carried out by limiting the trade in the leaves to government shops or licensed traders. Generally speaking such measures as are

adopted in many countries to prevent excessive consumption of alcohol and illegal trade in alcohol may be sufficient.

Lande, The International Drug Control System, supra note 14, at 129; see id. at 52-53.

[Footnote 77] The third draft of the treaty included separated cannabis leaves within the definition of "cannabis." The delegate from India spearheaded the opposition to this provision. In India cannabis leaves are used in preparation of a beverage called "bhang" which, like beer in this country, is consumed for nonmedical purposes. Tr. at 44-45, 196; see 39 FED. REG. 23074 (1974); NATIONAL COMMISSION ON MARIHUANA AND DRUG ABUSE, supra note 70, at 234.

Given the background of the relevant treaty provisions, we conclude that the Single Convention would allow the United States to place separated marihuana leaves in CSA Schedule V. The Acting Administrator agreed with this conclusion as an abstract legal principle; however, he broadened the inquiry and held that, in any event, he would not exercise his discretion to transfer marihuana leaves from CSA Schedule I to Schedule V. Specifically, he stated:

* * * If the Acting Administrator were faced with this question in the framework of an academic discussion, he might agree that Schedule V controls

[559 F.2d 754] could technically so limit separated leaves (and seeds capable of germination) as to meet the

bare bones language of the treaty.

However, marihuana in the illicit traffic is a mixture of crushed leaves, flowers, and twigs, and THC can be extracted from the leaves to make hash oil. Thus, the misuse to which the

leaves can be put and the form in which marihuana appears illicitly, make it obvious that Schedule V controls, which permit over-the-counter sales for a "medical purpose"

would fall far short of the contemplated restrictions and purposes of the Single Convention

and the intent of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970.

40 FED. REG. 44167 (1975); see id. at 44168.

The Acting Administrator's determination that CSA Schedule V controls are inadequate because of the usual composition of "marihuana" in this country is not, strictly speaking, a judgment regarding the degree of control mandated by the terms of the treaty. Indeed, the treaty itself makes a distinction between cannabis and separated cannabis leaves. [Footnote 78] Accordingly, this court must decide whether to uphold the Acting Administrator's decision as an exercise of his discretion within the latitude allowed by the treaty.

[Footnote 78] ALJ Parker rejected the argument later adopted by the Acting Administrator, stating that it

overlooks the obvious fact that the Single Convention

makes the precise distinction which the Government claims should be disregarded. When the leaves appear in a mix with the tops of cannabis, they are "cannabis" and are subject